The release of Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s (AOC) new clothing line has of course sparked plenty of controversy on social media. Yet, politically affiliated clothing is hardly novel. The political nature of AOC’s apparel is little different than President Trump’s MAGA hats. When someone puts on a shirt that says “Tax the Rich: AOC” they are communicating a similar message to that of the person wearing a red “Make America Great Again” hat. Both articles of clothing declare allegiance to one’s in-group and their disaffection with the respective out-group. Clothing has a distinctly political nature even outside of these conventional political spheres. For example, to mask or not to mask has become highly politicized in a way that nobody could have predicted.

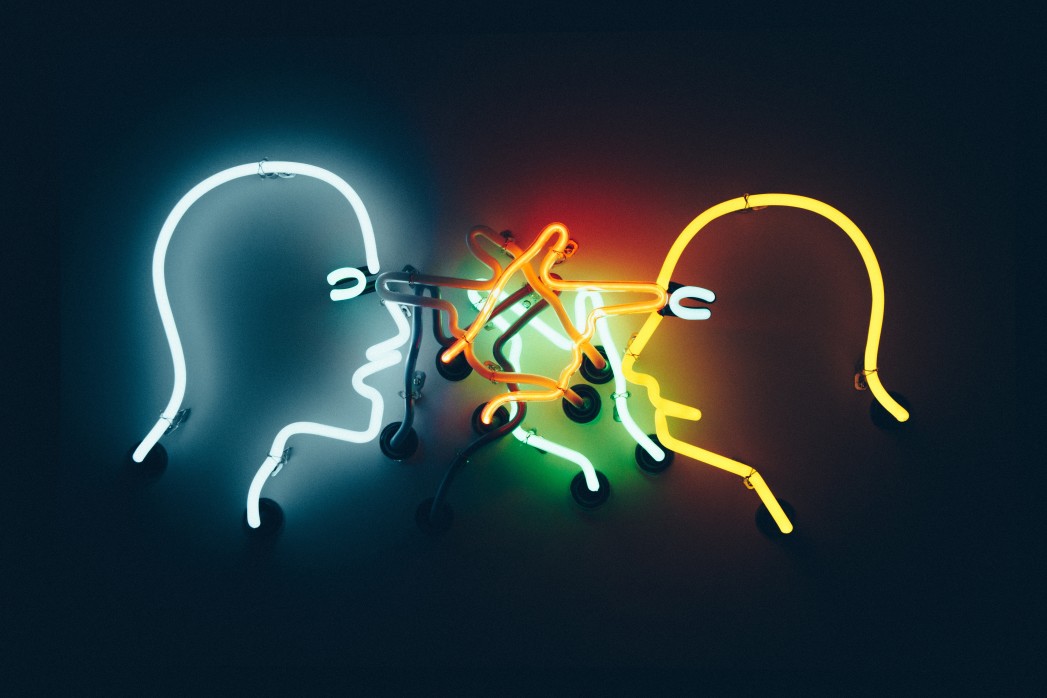

The way that we think about clothing in contemporary culture comes with the assumption that the autonomous individual independently purchases and clothes themselves. However, what we wear represents broader political and social forces like so many other seemingly personal aspects of our lives. We come into this world naked and it is only through society that we are clothed. Where liberalism is secured, what we wear is at the crossroads between the political and private realms. The average person dresses and prepares themselves for the judgements of society. Our clothing is in fact the politics that we wear.

I grew up in a highly politicized fringe Evangelical movement. My seven sisters and I wore long skirts or dresses, head coverings, and grew out our hair. All of this was done to signal, not only our religious views, but also our political significance. To our family and community, being girls who wore dresses and never pants was as politically significant as burning a bra in the street. Our politics were worn explicitly every time we left our house. When Betty Friedan and other second wave feminists shouted “the personal is political,” my community implicitly agreed and adopted the same sentiment for their own creeds. Clothing in the context of the culture war is not about the individual. It is about preparing for battle.

Both sides of the political isle seem to misunderstand the political significance of clothing. It is usually understood through the lens of oppression by left leaning activists — particularly within the feminist movement. In contrast, right leaning groups have tended to see attire as an apolitical subject that needs to be defended from those who would make it political. Both approaches ignore the possibility that clothing can be political without being corrupt. Clothing understood as political does not automatically make it a symbol of oppression or a sign of lost ground in the culture war.

The political significance of clothing is not a phenomenon unique to the American culture war. Clothing has played a role in politics throughout history. In Julius Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico, he dwells on the allegedly outré attire of Celtic and Germanic peoples as a way of demonstrating the otherness of enemy tribes. Dress establishes an explicit us versus them mentality. Caesar’s depiction of his opponents was politically motivated to favor his cause, but the emphasis on dress speaks to a broader truth in politics. As tribalism increases in American politics, a similar portrayal of difference is communicated through attire. What we wear communicates who we are for and who we are against.

Within the aristocratic systems of Western Europe, clothing also played a central role in establishing difference. For example, Dr. Michelle Beer highlights the political significance of clothing for Margaret Tudor by arguing that “clothing publicly proclaimed her identity” and her political significance as Queen of Scotland. Clothing not only distinguished the aristocrat from the commoner but also rank within the aristocracy. In a democracy without titles of nobility, we are left with brand names and the latest trends to distinguish rank. Today, what we wear continues to allow us to distinguish between groups and roles within groups. This can be as explicit as AOC’s new fashion line or as subtle as Carhartt’s streetwear takeover.

The mask as a political symbol in 2020 was used as a campaign tool by both Donald Trump and Joe Biden. The political polarization around mask wearing came as a surprise to many Americans. At first, Conservatives overestimated the threat of coronavirus and Liberals played it down; now, the roles have completely switched. What we wear has become even more meaningful, either through wearing or not wearing a mask. When we are deprived of more substantive ways to communicate with both our in-group and our out-group, people use clothing to communicate political allegiances and commitment to tribes.

The goal here is not to eliminate difference in dress in hopes of removing the political component. The very idea of everyone dressing the same sounds more Orwellian than practical. Rather, it is to bring awareness to the personal and political nature of our clothing.

We should be asking ourselves why we choose to wear something and if the message it sends is one intended to reach across lines or further enforce them. Are we dressing to further our differences and prepare for battle, or are we dressing to meet difference with kindness? Clothing can be used as a tool to further the culture war or it can be a means to seek peace. Both the MAGA hat and AOC shirt are about establishing difference and not seeking reconciliation. The goal is to be mindful of the political nature of our clothing, even when it seems apolitical. It is through increased awareness and sensitivity that our political engagement can become more intentional and productive.